No 51 - 2015

Hospital-acquired urinary tract infection

Hospital-acquired urinary tract infection

Henceforth, hospital-acquired urinary tract infections are monitored through the Hospital-Acquired Infections DataBAse (HAIBA), EPI-NEWS 9/15. HAIBA was launched in the spring of 2015 with presentation of hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infections, EPI-NEWS 10/15, and bacteraemias, EPI-NEWS 11/15.

HAIBA automatically collects patient-administrative data from the National Patient Register (NPR) and results from urine cultures from the Danish microbiology database (MiBa). By combining these data, it is possible to estimate the number and incidence of hospital-acquired urinary tract infections. Subsequently, data will be added on antimicrobial treatment from the regional medicine modules.

Background

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most frequent hospital-acquired infections. Prevalence studies have established that UTIs constitute between a fourth and a third of all infections acquired during admission. Risk factors for UTI include use of urinary catheters (particularly prolonged use), prolonged bed rest, sedation, urine retention and incontinence. Women and elderly patients are at increased risk. Predisposing factors also include foreign bodies and urinary conditions, generalised weakness and a range of systemic conditions.

Hospital-acquired UTI can lead to increased morbidity and mortality as the infection may progress into, e.g., pyelonefritis and bacteraemia. Hospital-acquired UTI is frequently associated with a prolonged admission period and increased treatment costs. Monitoring of hospital-acquired UTI is necessary, among others to follow the effect of the recommended measures to counter UTI (national Danish infection hygiene guidelines)

Case definition and classification

To identify patients with hospital-acquired UTI, a case definition was prepared that identifies UTI episodes and classifies them as hospital-acquired:

- Laboratory-diagnosed UTI: one or more urinary tract samples taken simultaneously that test positive for a maximum of two micro-organisms and of which a minimum of one of the micro-organisms shows growth of at least 104 colonies/ml urine.

- Hospital-acquired UTI: a laboratory-diagnosed UTI for which the sample was taken between 48 hours after admission and 48 hours after discharge.

- HAIBA only includes new episodes, defined as a hospital-acquired UTI that has a sample date more than 14 days after the latest positive test. This definition applies regardless of the micro-organisms detected.

The incidence is calculated as the number of urinary tract infection episodes per 10,000 days-at-risk. Days-at-risk are calculated as the number of days that pass from 48 hours after admission to 48 hours after discharge, or until a urinary tract infection presents. Only the first urinary tract infection episode of any admission is included in the incidence calculation. When a patient is re-admitted as part of a new treatment course, an UTI episode may occur, provided the above criteria are met.

The reason why only the first episode per admission course is included is that the risk of acquiring additional UTIs during the admission does not remain the same after the patient's first infection. This may be due to several factors, e.g. antibiotics treatment of the first UTI or that the patient is more exposed to infections.

The reason why the definition stipulates a maximum of 2 micro-organisms is that if more are found, this indicates that contamination has occurred.

The HAIBA data are presented at eSundhed, where the case definitions and data basis are also described in more detail.

Comparison of HAIBA and other data sources

Prior to the introduction of HAIBA, hospital-acquired UTI were monitored through prevalence studies. Compared with data from prevalence studies in the Capital Region of Denmark and in Region Zealand from the autumn of 2012 and the spring of 2013, HAIBA had a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 95%. Furthermore, HAIBA detected a number of additional cases that had not been included in the prevalence studies, primarily because the test results were not yet known at the time the prevalence study was conducted. Other reasons why the use of HAIBA detected more cases was that some findings of bacteriuria were assessed as being irrelevant by clinicians, e.g. because the urine sample had been collected through a urine catheter or because the patient was symptom-free.

HAIBA data were also validated with reference to incidence data from the Task Force of the Capital Region of Denmark, data from the HAIR project at Lillebælt Hospital and data from the Department of Clinical Microbiology in Aalborg. Overall, the conclusion following these validations is that the figures from HAIBA aremore specific than most regional reports and that the number of hospital-acquired UTI may be reported in various ways (due to differences in basic case definitions).

Examples of such differences include if:

- only one infection is counted per patient per admission (HAIBA only includes the first infection)

- urine collected from a flask, bedpan or bag is accepted as sample material (HAIBA does not accept these, but does accept catheter urine or unspecified “urine”)

- information about antimicrobial treatment forms part of the algorithm (HAIBA does not currently employ such information as it is not available nationally).

In other words, discrepancies are to be expected and may be explained by reference to different definitions and assumptions. Overall, we conclude that HAIBA offers more specific data than most regional reports.

Results

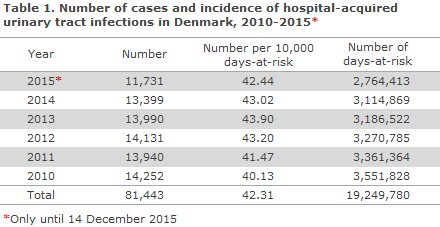

In the period from January 2010 to 14 December 2015, HAIBA identified a total of 81,443 cases of hospital-acquired UTI at Danish hospitals (public as well as private), Table 1.

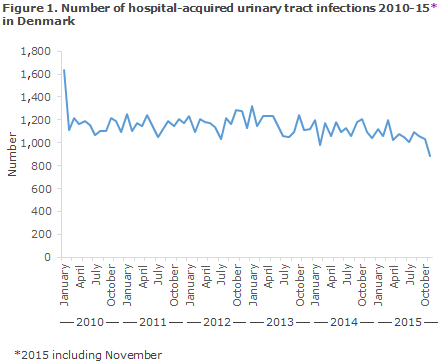

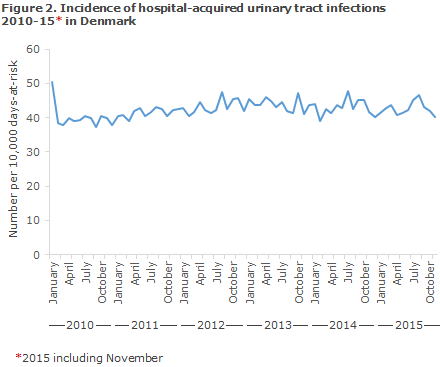

Figures 1 and 2 present the number and incidence for hospital-acquired UTI in Danish hospitals. In the 2010-2014-period, the number of cases remained stable at around 1,100 cases per month, whereas a slight increase in incidence was observed. It should be noted that the higher number and incidence observed in the beginning of 2010 and the decline at the end of 2015 are not real, but may be explained by the time at which calculations began and by delays relating to the latest data.

Commentary

In contrast to prevalence studies, HAIBA is based on automatic, daily data capture and requires no active reporting of data as the results are generated on the basis of updated data from MiBa, the patient-administrative systems and, in the future, also from the regional medicine modules.

The incidence of hospital-acquired UTI is stated as the number of cases and as incidence per week, month and year. It is therefore possible to calculate baselines locally and to study trends in the occurence of hospital-acquired UTI for each hospital and department. Generally, a slight increase in incidence is observed, which may be explained by a decrease in the number of days-at-risk owing, among others, to shorter admission periods.

The number and incidence vary between regions, hospitals and departments because of different practices for collection of urine samples, antibiotic treatment and different patient population compositions. Some patient groups have a particularly high risk of UTI. Other things being equal, departments traditionally diagnosing UTIs using urine stix will report a lower incidence than departments using urine culture as their standard operating procedure. Furthermore, departments that diligently perform control cultures will detect more infections than departments that do not. Nevertheless, we believe that this latter source of error is of limited significance as HAIBA includes only one infection per patient per treatment course.

Samples based on catheter urine are an important potential pitfall. Due to the available data, HAIBA cannot currently distinguish urine samples that were collected correctly (e.g. midstream urine) from samples drawn by catheter, for example. This issue may be solved by a correct and uniform national-level use of order codes (MDS codes) when samples are submitted for microbiological diagnostics. Furthermore, uniform national-level use of the codes would facilitate, e.g., stratification by sample material and possibly in time also stratification by risk patients.

Systematic use of information about antibiotics treatment from the regional medicine modules is another manner in which HAIBA may be improved. By employing this information in combination with culture findings, the algorithm may be refined. It is the intention to improve HAIBA as described above. Until these methodological issues are solved, it is important to be aware that while HAIBA reports may be used as indicators when assessing a trend at a department or a hospital, the reports may not be used to determine or compare the disease burden across hospitals or departments or for benchmarking.

For HAIBA to become a successful tool, it is important that the results are used actively. As mentioned previously, EPI-NEWS 9/15, HAIBA cannot explain why the observed prevalence is as it is, or why changes occur. But dissemination of data through HAIBA may hopefully trigger discussions as to possible explanations and may stimulate studies to better understand the results and to initiate new measures to strengthen the prevention of infections at hospitals.

(S. Gubbels, L. Espenhain, O. Condell, J. Nielsen, K. Mølbak, M. Voldstedlund, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, B. Kristensen, Department of Microbiology and Infection Control, K. S. Nielsen, Danish Health Data Authority, J. Anhøj, Centre of Diagnostic Investigation, Rigshospitalet, S.C. Rasmussen, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Hvidovre Hospital, H.C. Schønheyder, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Clinical Diagnostics, Aalborg University Hospital, J.K. Møller, J. Redder, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Hospital Lillebælt, Vejle Hospital, B. Lundgren, Centre of Diagnostic Investigation, Rigshospitalet, J. Utzon, Centre for Health, Unit for Quality and Patient Safety, Capital Region of Denmark, J. Engberg, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Slagelse Hospital, P.D. Cramon, Region Zealand, S. Ellermann-Eriksen, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Aarhus University Hospital, E. Lyngsø, Corporate Quality, Regionshuset Viborg, Central Denmark Region, A. Holm, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Odense University Hospital, J. Kjær-Rasmussen, Healthcare Planning, Patient Dialogue and Quality, North Denmark Region)

Merry Christmas & Happy New Year

Unless special circumstances arise, EPI-NEWS will not be published until week 1, 2016.

The Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology wishes everyone a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.

(Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology)

Link to previous issues of EPI-NEWS

16 December 2015