No 49b - 2025

Tularemia in Denmark 2025

Tularemia in Denmark, 2025

- As of 31 October 2025, a total of 32 laboratory-confirmed cases of tularemia had been registered at Statens Serum Institut, corresponding to an incidence of 0.54 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.

- The majority of cases occurred among men. Across sexes, the age group 40–69 years was the most affected.

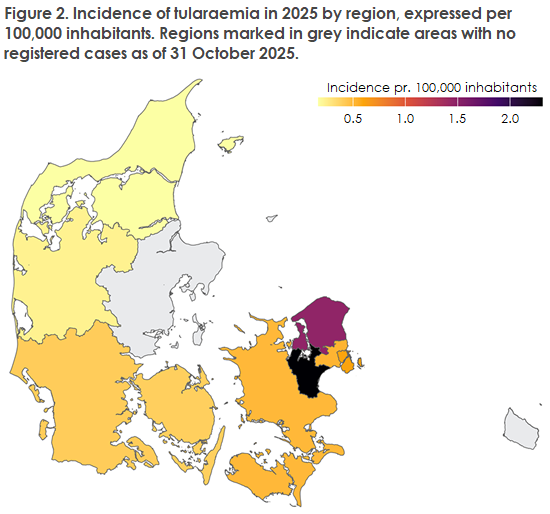

- All five Danish regions have reported cases in 2025. Distributed by province (landsdel), North Zealand had the highest total number of cases (seven in total).

- Most cases (38%) occurred in August and September, with six cases registered in each month, consistent with previous years.

- All PCR- or culture-positive isolates were confirmed as Francisella tularensis ssp. holarctica and were susceptible to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline/doxycycline as well as gentamicin and rifampicin.

- Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) showed that most isolates belonged to different clades and subclades, indicating that no single dominant clone is circulating.

Tularemia

Tularemia, also known as rabbit fever, is a highly infectious disease caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis. It primarily affects hares, rabbits, and rodents, but other wild animals such as squirrels may also become infected. Transmission to humans can occur vector-borne via tick bites or mosquito bites, but infection may also arise after handling live or dead infected animals or their blood, after ingestion of contaminated drinking water or insufficiently cooked game meat, via inhalation of water droplets or dust contaminated with the bacterium, or through contact with contaminated materials in the environment. Human-to-human transmission has not been reported. Hunters, farmers, and individuals engaged in outdoor recreational activities are considered to be at increased risk of acquiring tularemia.

The infection typically presents with non-specific symptoms such as headache, chills, high fever (39.5–40°C), and marked fatigue, followed by specific manifestations depending on the route of infection. The incubation period is usually 3–5 days but may vary from 1 to 21 days.

Francisella tularensis type B (F. tularensis ssp. holarctica), which occurs in Denmark, generally causes milder disease compared with type A (F. tularensis ssp. tularensis), the more virulent form that occurs naturally only in North America. Disease presentation depends on the route of infection, as outlined below.

Epidemiological overview, 2013–2024

With the revision of the “Executive Order on Notification of Infectious Diseases” in autumn 2023, it became possible to monitor tularemia via MiBa, and clinical microbiology departments were required to submit isolates to SSI for further characterization. The overview below covers the period 2013–2024, for which data were available through MiBa. The extent to which tularemia may be underdiagnosed is unknown.

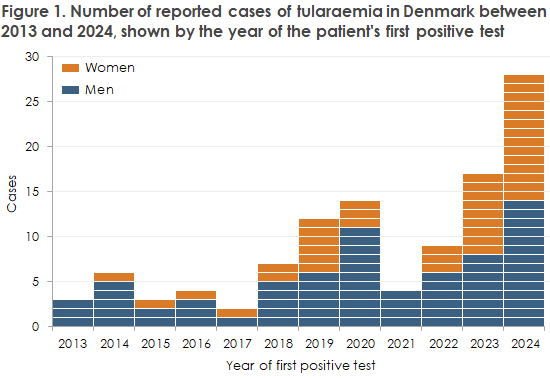

During 2013–2024, Danish laboratories confirmed a total of 109 human cases of tularemia, with a marked peak in 2024 when 28 cases were reported, Figure 1. A strong increase was also observed at EU level, where Member States reported an 89% rise in human tularemia cases in 2023 compared with 2022, bringing the total number to 1,185 cases. More than half of these cases (651) were reported by Sweden, followed by Finland and Germany, each reporting 103 cases.

Tularemia, January–October 2025

In 2025, as of 31 October, 32 cases of tularemia had been confirmed, corresponding to an incidence of 0.54 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Patterns regarding demographics, place of residence, and seasonal variation for the confirmed cases are presented below:

- Sex and age distribution: Men accounted for 20 (63%) of tularemia cases. The most affected age groups were men aged 50–69 and women aged 40–49, representing 70% (14/20) and 58% (7/12) of all reported cases, respectively.

- Geographical distribution: Tularemia cases were diagnosed from all five Danish regions and from nine of the country’s 11 provinces. The highest number of cases was registered in North Zealand (seven in total). East Zealand had the highest incidence with 2.3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, Figure 2. It is important to note that information on where the infection was actually acquired is not available. Therefore, region of residence is used as a proxy for site of infection.

- Seasonal variation: A seasonal pattern was observed, with case numbers and test submissions increasing during the summer months and peaking in August and September (six cases in each month). This pattern is consistent with previous observations.

Vector-borne transmission is believed to play a significant role in the acquisition of tularemia in Denmark, although some patients have reported direct contact with infected animals or exposure to potentially contaminated aerosols.

For a detailed epidemiological description of surveillance results for 2013–2024.

Phenotypic and genotypic characterization

All PCR- or culture-positive isolates were confirmed as F. tularensis ssp. holarctica.

All culture-positive isolates were susceptible to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline/doxycycline—the primary antibiotics for treating tularemia—as well as gentamicin and rifampicin. All culture-positive isolates were submitted for WGS and genotyped using canSNP nomenclature.

Seven isolates from 2024 belonged to different subclades: five to the larger B.12 clade (Biovar II) and two to the B.6 clade (Biovar I).

Of the six isolates submitted in 2025 so far, three belonged to subclade B.103 (a subclade of B.12) and originated from different regions of Denmark. Subclade B.103 has previously been detected in Denmark—once in 2024 and once in 2022.

The remaining isolates belonged to the B.6 clade: two were classified as subclade B.146 and one as subclade B.151. None of these B.6 subclades have been previously identified in Denmark. All B.6 isolates came from patients residing in North Zealand.

Clinical manifestations

Symptoms of tularemia vary depending on the route of infection:

- Ulceroglandular tularemia. The most common clinical form, often arising after tick bites, mosquito bites, or direct contact with infected animals or contaminated material through damaged skin. A primary ulcer (ulcus) develops at the inoculation site, which may become pustular and ulcerate, or in some cases heal quickly and remain unnoticed. Regional lymph nodes become markedly enlarged and tender, with risk of rupture and suppuration if untreated.

- Glandular tularemia. Similar to the ulceroglandular form but without the characteristic primary ulcer.

- Oculoglandular tularemia. Involves unilateral conjunctivitis and enlargement of regional lymph nodes, typically following direct inoculation of the conjunctiva via contaminated fingertips or, more rarely, aerosol exposure.

- Oropharyngeal tularemia. Occurs after ingestion of contaminated food or water and is associated with painful swallowing. The primary lesion is located on the oropharyngeal mucosa, and cervical lymphadenopathy is common. Associated symptoms may include sore throat and gastrointestinal discomfort.

- Pulmonary tularemia. Caused by inhalation of F. tularensis or hematogenous spread from another primary focus. Patients may present with symptoms consistent with pneumonia, including dry cough, substernal pain, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnoea, as well as imaging findings of pulmonary infiltrates and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

- Typhoidal tularemia. A severe systemic disease without an identifiable entry point, characterized by high fever, marked fatigue, and signs of systemic infection.

Diagnostics and notification

F. tularensis can be detected using specific PCR, metagenomic methods (e.g., 16S rDNA PCR), or culture.

In the early phase of the disease, PCR and culture can be performed on material (biopsy/pus) from the primary lesion in ulceroglandular or glandular tularemia. In later stages, biopsies or aspirates from enlarged lymph nodes or abscesses may be examined. Typhoidal tularemia is diagnosed by growth of F. tularensis from blood culture bottles.

F. tularensis has specific growth requirements, and a negative culture result does not exclude tularemia. Because of the risk of laboratory-acquired infection, the local clinical microbiology laboratory must be informed if tularemia is suspected, and samples must be handled accordingly.

The diagnosis can also be made using serological methods. During the acute phase, serology is often negative. A single serum sample with a titre ≥100 supports the diagnosis of tularemia, while a fourfold rise in antibody titre over a period of 2–3 weeks (between acute and convalescent samples) is considered confirmatory evidence of infection.

Tularemia has been a laboratory-notifiable disease in Denmark since November 2023. Isolates of F. tularensis, as well as primary samples in which the bacterium has been detected and material considered to contain amplified organism (e.g., blood culture bottles, pure colony material on eSwab or similar), must be submitted to SSI according to regulations for infectious substances (UN 2814/Category A transport). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing and further characterization by whole-genome sequencing (WGS) are performed on all submitted isolates.

Primary clinical material submitted for PCR, and potential culture if tularemia is suspected, must be sent to SSI under UN 3373 guidelines, i.e., as standard clinical samples (Category B transport).

Prevention

No vaccine is available for the prevention of tularemia. The risk of infection can be reduced through preventive measures when spending time in nature. Such measures include minimizing tick bites and mosquito bites by using repellents and wearing long-sleeved clothing and trousers; using gloves or avoiding contact with sick or dead wild animals and their tissues, including dried blood, as well as contaminated surfaces; thoroughly cooking game meat before consumption; and avoiding drinking untreated surface water.

For laboratory personnel, appropriate personal protective equipment should be used when handling samples suspected to contain F. tularensis.

(A.P.F. Canabarro, L. Espenhain, S. Ethelberg, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention; A. Ronayne, Department of Bacteria, Parasites and Fungi; C.S. Jørgensen, Department of Virology and Microbiological Preparedness)