No 50 - 2019

Reminder letters concerning lacking childhood vaccinations

New website about congenital diseases for parents and health workers

Purulent meningitis 2018

Reminder letters concerning lacking childhood vaccinations

The Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention receives a number of enquiries about apparently erroneous reminder letters sent out under the new 2019 reminder scheme.

The reminder scheme is described in EPI-NEWS 34/19 and 42-43 /19.

Under the new scheme, children who

- were born on 1 August 2019 or later

- turn 4 years old as from 1 November 2019

- turn 12 years old as from 1 November 2019

will automatically be allocated childhood vaccinations relevant to their age as part of the “recommended vaccination programme” in the Danish Vaccination Register (DVR). Two weeks before the scheduled time of any childhood vaccination, the parents will receive an e-Boks message reminding them to schedule an appointment for vaccination. One month after the planned vaccination time, a reminder will automatically be sent out if the vaccination has not been given.

When registering vaccinations, it is important to do so in accordance with the list of recommended vaccination courses. When opening the vaccination course to which the child is subscribed, all vaccinations planned for the child will be listed along with recommended vaccination dates. The current vaccination is registered within the course, by marking the vaccine as “given”. When the vaccine is registered as described, the vaccine automatically moves up the list and is displayed as a vaccine that has been given today, and all you need to do is to record its batch number.

Furthermore, the dates of any subsequent vaccinations in the vaccination course are automatically adjusted.

If you do not register the vaccination as described above but rather register e the vaccination independently of the course, the child’s parents will receive a reminder letter one month later, letting them know that the vaccination has not been registered. In these cases, general practice needs to edit the recommended vaccination course to avoid unnecessary reminders being sent to the parents.

Registration of vaccinations is described in broad terms in the section “Mainly for health workers” at the SSI’s website. All medical practice systems have the “recommended vaccination courses” integrated in their vaccination list. What the list is called may vary from one medical practice system to the next. It may thus be called “Planned vaccination courses”, “Planned vaccination programmes”, “Recommended vaccination programmes”, etc.

(T.G. Krause, L.K. Knudsen, Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention)

New website about congenital diseases for parents and health workers

Today, Statens Serum Institut (SSI) launches the new website www.ssi.dk/nyfoedte (in Danish language) with information for parents and health workers about the Danish screening programme for congenital diseases.

99.5% of all parents currently accept the offer of having their child tested upon birth for a number of serious and in the most serious cases disabling and life-threatening conditions. As from 1 February 2020, the screening is expanded to include the serious immune deficiency SCID. Thereby, the programme will comprise a total of 18 conditions.

Section for health workers

All of the conditions in the programme share a common aspect; they are all treatable if diagnosed in time. That means that the heel pad blood sample must be taken both correctly and timely - after which it must be sent to the SSI in a safe and rapid manner. The new website therefore carefully explains and illustrates e.g. where on the heel the sample is taken, where the blood stains must be placed on the filter paper, and how to ensure that the sample reaches the SSI timely. One of the sections that was prepared specifically with health workers in mind provides information about interpretation of test results and detailed descriptions of the conditions.

Section for parents

Some parents will definitely feel safe, simply from knowing that their child is screened for a number of congenital conditions. Others want to learn more. The latter group may now - preferably in good time before giving birth - learn more about the screening programme, how screening is performed, and what will happen if results show that your child may be affected by one of the conditions. The website also includes a section explaining how the sample is stored at the SSI and for what it is subsequently used.

Visit the new website at ssi.dk/nyfoedte

FACTS about the screening programme for congenital conditions

- The screening programme was established in 1975 when only a single condition was included, phelylketonuria (PKU). Subsequently, the programme has been expanded as is has become possible to diagnose and treat more conditions.

- Every year, the SSI receives approx. 62,000 neonate samples.

- It is not possible to determine if a neonate has one of the 17 conditions by examining it. These conditions only present later, and then the affected children become seriously ill and the conditions may cause permanent sequelae and are furthermore difficult to treat.

- Approx. 2 million analyses are performed every year.

- Today, the screening includes a total of 17 conditions that can all be treated provided they are diagnosed in time. As from 1 February 2020, the screening programme will count 18 conditions.

- The screening programme cannot establish 100% if a child has a congenital condition. But the screening indicates that further tests are warranted to establish if the child is affected or not.

Purulent meningitis 2018

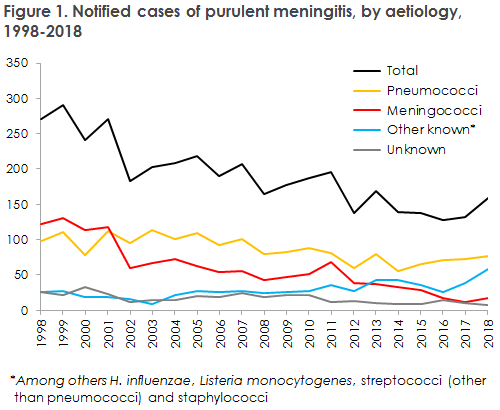

- 2018 saw a total of 159 notified cases of purulent meningitis.

- A small increase was observed in the number of patients with purulent meningitis compared with the 2014-2017 period (128-134 cases).

- The increase in cases was observed among the very youngest (<1 year) and among the older age groups.

- Meningitis caused by pneumococci was in line with the previous year.

- Following a strong increase in the number of cases caused by Haemophilus influenzae in 2017 (14 cases) as compared with the previous years (1-3 cases), the number dropped to eight in 2018. Three cases were caused by type b, including one fully vaccinated child.

- An increase was observed in the number of cases caused by streptococci compared with the previous year.

- In more than half of the notified cases of purulent meningitis, the affected person had underlying disease or risk factors.

Meningococcal meningitis (17 cases) in 2018 is described in EPI-NEWS 40/19 and in the 2018 Annual Report on meningococcal disease.

A small increase was observed in the number of patients with purulent meningitis compared with the 2014-2017 period (128-134 cases). The majority of the cases were caused by streptococci (48%), other streptococci (mainly group A and B streptococci) (15%) and meningococci (11%). H. influenzae and L. monocytogenes accounted for 5% and 7%, respectively. Other pathogens were seen in 9% of the cases, including: S. aureus, E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae and M. catharrhalis/nonliquefaciens. In a total of seven cases (4%), patients were notified on the clinical picture and/or cerebrospinal fluid cell counts consistent with purulent meningitis, but without detection of bacteria by culture or PCR.

In all, 77 cases of pneumococcal meningitis were observed. Among these, 13 patients were below 18 years of age. Vaccine failure was not seen, but one child had received one Prevenar13 vaccination.

Meningitis caused by H. influenzae declined following a sudden increase in 2017 (from 1-3 annual cases to 14 annual cases), to eight cases in 2018. Three cases were caused by type b, including one fully vaccinated two-year-old child.

Monitoring of meningococci and pneumococci is estimated to be nearly complete. For the more rare causes of purulent meningitis such as staphylococci and E. coli, a discrepancy is recorded between the number of positive findings in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the number of clinical notifications. How large a share of the discrepancy may be explained by under-reporting remains unknown. In future, it is being planned to monitor purulent meningitis via CSF sample results in the MiBa rather than through clinical notification. However, findings of pathogens in CSF are not always acute meningitis as the samples may have become contaminated or the pathogens may be due to postoperative or post-traumatic infections that should not form part of the statistics on purulent meningitis. Furthermore, the recording of sample material and indications are not done unambiguously or homogeneously in the departments of clinical microbiology, and it is therefore not possible to distinguish with certainty CSF from lumbar puncture and from intracranial drainage or valves. The SSI will therefore explore the discrepancy further and assess how the monitoring may be done most expediently in future.

(S.S. Voss, P. Valentiner-Branth, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention, S. Hoffmann, H-C. Slotved, T. Dalby, K. Fuursted, Department of Bacteria, Parasites & Fungi