No 27a+b - 2017

Recommended vaccinations for foreign travel

Pilgrimages to Mecca

Increase in infections with invasive group A streptococci in January-April 2017

Recommended vaccinations for foreign travel

Statens Serum Institut’s (the SSI) reference group for travel vaccination and malaria prophylaxis regularly revises the SSI’s travel vaccination recommendations. A number of country-specific updates have been made to the annual summary table, EPI-NEW 27b/17. All changes have been updated on the SSI’s travel site.

This year, the reference group has primarily focused on the risk of malaria when travelling to Southeast Asia and to Central & South America and on the indication for vaccination against tuberculosis. In addition, the group has looked into the duration of protection following primary vaccination against meningitis with conjugate meningitis vaccines and following booster vaccination against Japanese encephalitis. This work has led to the following updates to the recommendations.

Changed recommendation on malaria prevention for travellers to Southeast Asia and Central and South America

The risk that Danish travellers to Southeast Asia may become infected with malaria is very modest. In the past 10 years (2007-2016), a total of 69 persons have been recorded (equivalent to < 10% of all notified malaria cases) with malaria detected in Denmark following travels to all of Asia. More than 90% of these cases were acquired in India, Afghanistan or Pakistan, whereas only seven cases were acquired in Southeast Asia (Thailand, Myanmar and Indonesia), EPI-NEWS 26/17. The vast majority of the imported malaria cases from Asia, 90% (62/69), were due to vivax malaria, which usually has a relatively mild and benign course, whereas approximately 10% were due to falciparum malaria.

Furthermore, the low number of malaria cases imported into Denmark must be seen in light of the considerable number of Danish travellers to Southeast Asia, which is visited by more than 200,000 Danes annually. It remains unknown how many of these travellers take malaria medication during their travel, but the majority typically travel for 1-2 weeks to areas where chemoprophylaxis is currently not recommended (but where mosquito bite prophylaxis may be used, which also protects against other mosquitoes, including day-biting mosquitoes, EPI-NEWS 6/12). Even in areas where the risk is so high that chemoprophylaxis has so far been recommended, the risk of becoming infected with malaria is generally very low compared with the risk when travelling to Africa. This is because the transmission intensity of malaria outside of Africa in general is at a considerably lower level, in Southeast Asia and Central & South America alike.

Stated in the same manner and for the same period as for Asia, as little as eight imported malaria cases were recorded from Central & South America, corresponding to 1% of all imported cases. Hereof, three cases were caused by Plasmodium falciparum and five by Plasmodium vivax, EPI-NEWS 26/17. Although the number of Danish travellers to this continent is substantially lower than the number visiting Southeast Asia, the malaria risk is generally considered to be lower or in line with the Southeast Asian risk level.

Various other European countries, including Switzerland and Germany, do not generally recommend medication-based prophylaxis for common tourist travellers to either Southeast Asia or Central & South America, apart from travellers to specific areas that have a particularly high risk.

On this basis, Statens Serum Institut no longer recommends routine use of chemoprophylaxis for travellers to the majority of the countries/areas in Southeast Asia and Central & South America where such prophylaxis was previously recommended.

For travellers to specific areas with a known certain level of risk of malaria, stand-by emergency treatment may be used as an alternative to conventional malaria prophylaxis, see below.

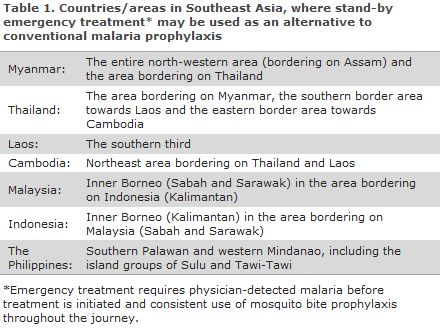

Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, this applies to travellers visiting Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines, Brunei and Indonesia, Table 1.

A summary map of malaria prophylaxis for Southeast Asia is available here (in Danish).

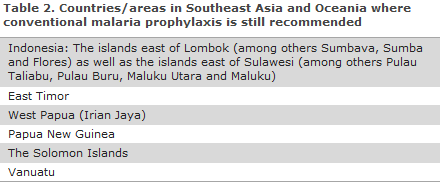

The recommendation concerning routine use of chemoprophylaxis remains in place for all travellers to a number of eastern Indonesian Islands (excluding Bali and Lombok), to West Papua/Irian Jaya and to Papua New Guinea, The Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, which geographically belong to Oceania, Table 2.

The recommendations for travellers to the Indian subcontinent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan) also remain unchanged, EPI-NEWS 27b/17.

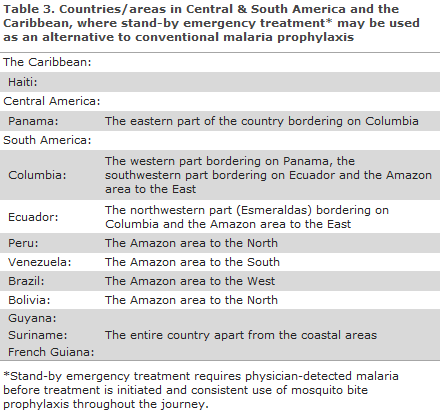

Central & South America (and the Caribbean)

In Central America, where almost all malaria is chloroquine-sensitive, no areas remain to which chemoprophylaxis is recommended, but mosquito bite prophylaxis is still recommended; this with the exception of the easternmost part of Panama that borders on Colombia.

This also applies to travellers to South America where travellers to known risk areas, as is the case for Southeast Asia, may be provided with stand-by emergency treatment as an alternative to chemoprophylaxis, see below. This applies for travellers to parts of the Amazon area and to other specific areas and to Haiti, Table 3.

A summary map of malaria prophylaxis for Central & South America is available here (in Danish).

Whether chemoprophylaxis is omitted or not, it is very important that the traveller is informed that some risk of malaria may remain, and the traveller must therefore be recommended systematic use of effective mosquito bite prophylaxis and must be instructed to be attentive to fever and other malaria symptoms both during and after the travel (particularly in the initial three months after returning from the travel).

Stand-by emergency treatment

The following is recommended as stand-by emergency treatment (for adults): atovaquone/proguanil, 4 tablets daily for 3 days (with a fat-containing meal).

Stand-by emergency treatment is handed out along with written instructions (in Danish) stating that the treatment should not be initiated before the traveller has seen a doctor and had malaria parasites detected in the blood.

It is important to point out that Stand-by emergency treatment is not the same as self-therapy. If the traveller runs a fever during a stay in Southeast Asia or Central & South America (or other places with a malaria risk), the traveller should always contact the emergency desk of his or her insurance company for advice on local malaria work-up and treatment.

Furthermore, it is important to be aware that some groups of travellers, e.g. immigrants who visit their families in their country of origin, travellers who go trekking and stay overnight in some jungle and swamp areas and back-packers on long-term travels with no predetermined travel route, may be at a heightened risk of becoming infected with malaria, and these groups therefore require extra careful guidance.

In the summary tables, EPI-NEWS 27b/17, the previous prophylaxis levels of Southeast Asia and Central & South America are still stated, but the symbol for Stand-by emergency treatment (X/n or x/n) has been added. The z/Z symbol was replaced by x/X as mefloquine is practically no longer used in Denmark, and guidance on prophylaxis in areas with known mefloquine resistance is therefore obsolete.

Other changes relating to malaria prophylaxis

Turkey: Mosquito prophylaxis no longer recommended.

All the other changes to risk areas and prophylaxis areas that were stated in the WHO’s latest issue (2017) of International Travel and Health were not implemented, owing to the changed recommendation concerning chemoprophylaxis for Danish travellers to Southeast Asia and Central & South America.

Yellow fever

Several countries have introduced a requirement for vaccination if the traveller is coming from a yellow fever area. This information is provided on the SSI’s travel site.

Currently, we recommend yellow fever vaccination for all travellers to Brazil above 9 months of age, EPI-NEWS 12/17.

BCG vaccination

The BCG vaccine’s protective effect in children until adolescence (11-12 years) is well-documented and good. Unfortunately, it has never been documented that BCG has any convincing effect against TB in adults, including healthcare workers who are at risk of occupational TB exposure. Nevertheless, experience shows that the risk for such workers is currently modest.

The BCG vaccine is a live attenuated vaccine, and side effects are frequent and sometimes severe. To avoid complications to the vaccination, it is important that the vaccine be administered intradermally and not subcutaneously. Furthermore, the vaccine should, to the extent possible, be administered by staff who have been trained to do so.

BCG is indicated:

- for new-borns, if their parents are from a TB-endemic area (incidence > 40 TB cases per 100,000 inhabitants). This is primarily because these children are at an increased risk of exposure to TB infection in Denmark.

- for children of immigrants who are under the age of 12 who will shortly be visiting relatives in TB-endemic areas

- children under 12 years of age who will be staying with their parents for a longer period of time (> 6 months) in TB-endemic areas.

BCG vaccination of adults should only be considered if there is a risk of being exposed to infection with particularly resistant TB (MDR/XDR-TB). Countries/areas with special resistance problems appear from the WHO’s Global TB Report. Nevertheless and as stated, the protective effect is uncertain, and if you decide to vaccinate adults, you must be aware that the vaccine produces a suppurating wound in the skin that may cause some discomfort in the course of the following 2-3 months.

The BCG vaccine is probably effective after approx. 1 month. Booster vaccination is not recommended.

For special groups who will have prolonged and close contact with the local population and patients in high-endemic countries, TB testing may be considered with the so-called gamma-interferon test before departure and then again two months after the traveller has returned, as conversion from a negative to a positive test result may trigger an offer of prophylactic TB treatment.

Meningitis

Nimenrix®:

The age indication is widened to include neonates as from the age of 6 weeks: The first vaccine may be given as from 6 weeks of age and the second dose must be given a minimum of 2 months later. A third (booster) dose is recommended at 12 months of age. Hereafter, the duration of the protection is as described in the following. In all cases, the dose is 0.5 ml.

Nimenrix® may, as previously, be used in children ≥ 1 year and in adults. A single dose is given. The approved summary of product characteristics (SPC) documents 5 years of protection following primary vaccination for the following age groups; 12-23 months, 2-10 years (however, only with a 44-month follow-up) and 11-25 years (and 11-17 years). In addition, other published data document 3 years of protection for the 11-55-year age group. Thus, for persons above 55 years of age, there are no data on the duration of protection following primary vaccination, but data are available to document that persons aged more than 55 years of age respond well to primary vaccination with Nimenrix (antibody measurements made one month after the vaccination).

Previous statements have assumed that the expected duration of protection is 5 years, EPI-NEWS 37/16. Although data are not available for all age groups, it may be expected that the protection will be comparable across age groups.

Menveo®:

As a registered conjugate meningococcal vaccine for use in infants is now available (Nimenrix®, see above), the previously used off-label indication for vaccination of infants aged 2-11 months with Menveo®, EPI-NEWS 37/10, no longer applies.

As previously, Menveo® may be used for children aged ≥ 2 years of age and for adults. A single dose is given. The SPC documents 5 years of protection following primary vaccination for the age groups 2-10 years and 11-18 years. For these age groups, data also support a high antibody response following booster vaccination. For persons over 18 years of age, SPC data are not available to document the duration of protection following primary vaccination.

Previous statements have assumed that the expected duration of protection is 5 years, EPI-NEWS 37/16. Although data are not available for all age groups, it may be expected that the protection will be comparable across age groups.

According to the SPC for both Nimenrix® and Menveo®, after 5 years a somewhat lower share have protective antibodies against group A antibodies than against the remaining three groups. The clinical significance of this is unknown, but if there is a special risk of exposure to the infection with group A meningococci, the SPC states that a booster dose may be considered already after one year. Nevertheless, both manufacturers have stated that currently at least, no meningococcal disease caused by group A has been observed globally among previously vaccinated persons (lack of efficacy), which supports that the persons who have received vaccination are, in fact, protected, regardless of the vaccine they have received.

Both vaccines may be used as booster vaccines for persons who previously received initial vaccination with the same or another conjugate meningococcal vaccine and with an (non-conjugate) polysaccharide vaccine.

Japanese encephalitis

The reference group has previously assessed that the JE vaccine Ixiaro® after boosting of basic vaccination may be assumed to protect for at least 5 years, EPI-NEWS 26a + b/15. Ixiaro® is now approved for 10-year protection following the first booster, usually given 12-24 months after the primary vaccination series.

(C.S. Larsen, Danish Society of Travel Medicine, S. Thybo, Danish Society for Infectious Disease, J. Kurtzhals, Danish Society for Clinical Microbiology, N.E. Møller, Danish College of General Practitioners, L.S. Vestergaard, Danish Society for Tropical Medicine and International Health, K. Gade, The Danish Paediatric Society, P.H. Andersen, A.H. Christiansen, Department of Infectious Epidemiology and Prevention)

Pilgrimages to Mecca

In 2017, the dates for the Hajj are 30 August-4 September.

Meningococcal disease:

To obtain a visa for Saudi Arabia, anyone doing a pilgrimage must have received the tetravalent vaccine against meningococcal disease of serogroups A+C+W135+Y no later than 10 days prior to entering the country, and the vaccine must have been administered within a 5-year-period. Nevertheless, if the international vaccination card does not document that a conjugate vaccine was administered, the validity is only three years.

In Denmark, two four-valent conjugate vaccines are registered for protection against meningococcal disease caused by group A, C, Y or W135; Nimenrix® and Menveo®.

Nimenrix®: The age indication is widened to include neonates as from the age of 6 weeks: The first vaccine may be given as from 6 weeks of age, and the second dose must be given a minimum of 2 months later. A third (booster) dose is recommended at 12 months of age. In all cases, the dose is 0.5 ml. Nimenrix® may, as previously, also be used in children ≥ 1 year and in adults.

Menveo® can be used in children aged ≥ 2 years of age and in adults. A single dose is given.

Influenza:

Influenza vaccination is not a requirement, but is recommended by the Saudi Arabian authorities, particularly in pregnant women, children below the age of 5 years, elderly persons and chronically ill persons. However, the influenza vaccine for the 2017/18 season will not be available until the end of September 2017.

Zika virus infection and dengue fever:

It has been many years since aedes aegypti mosquitoes were last confirmed in the Hajj and Umrah areas, but the mosquito does occur in the surrounding cities. The Ministry of Health of Saudi Arabia recommends that travellers to Hajj and Umrah use mosquito bite prophylaxis 24 hours a day in order to avoid mosquito-borne infections.

Furthermore, it is recommended that travellers observe standard hygiene advice, including:

- avoiding contact with persons suffering from acute infections of the respiratory tract

- maintaining good hand hygiene

- using a mask in case of acute airway symptoms

- avoiding close contact to animals, including camels (particularly contact to animal excretions such as saliva and faeces)

- avoiding ingestion of raw camel milk and fresh camel meat.

Persons who experience severe infection of the respiratory tract (fever with pneumonia and/or difficulty breathing) or other severe infectious disease in the first 14 days after returning from the Arabian Peninsula should see a doctor.

(A.H. Christiansen, P.H. Andersen, Department of Infectious Epidemiology and Prevention)

Increase in infections with invasive group A streptococci in January-April 2017

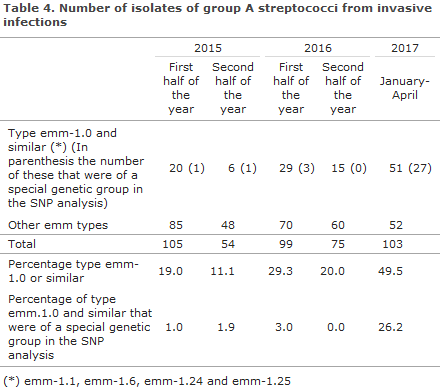

In the first months of 2017, an increased number of isolates of group A beta-haemolytic streptococci (GAS) has been received, Table 4. The increase was observed across Denmark. Among the submitted isolates, type emm-1.0 and related types comprised nearly 50% in January-April 2017 compared with 11-29% in the four preceding semesters in 2015-2016.

The Neisseria- and Streptococcal Reference Laboratory (NSR) receives isolates of beta-haemolytic streptococci (BHS), which have caused invasive infections, from the departments of clinical microbiology. The BHS are mainly detected in blood, muscle or spinal fluid. Submission is voluntary. The NSR performs molecular biology typing (emm-type) using whole-genome-sequencing (WGS). In particular, type emm-1.0 and related types (emm-1.1, emm-1.6, emm-1.24, emm-1.25, etc.) may exhibit increased virulence compared with other emm types. In order to further assess any relation between isolates of the same emm-type, they can be characterised by description of their genetic variations in the form of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP).

Owing to SNP analysis of GAS-type isolates of emm-1.0 and related types from the period from January 2015 to April 2017, the majority could be placed in a larger number of distinct groups. There were isolates from several regions in each of these genetic groups, and there was no unequivocal association between regions and groups. One of these genetic groups was practically only seen in 2017 as the group comprised 55% (27/51) of all emm-1.0 and related types in 2017, compared with only 8% in 2015 (2/26) and 7% in 2016 (3/44), Table 4.

Commentary

We would like to draw attention to the increased occurrence of type emm-1.0 and related types, which are often more virulent than other types. The background for the increase in GAS as the cause of invasive infections remains unknown, but it has affected all regions, both for all GAS, for type emm-1.0 and related types, and for the special genetic group. All GAS are fully sensitive to penicillin.

Continued submission of invasive GAS isolates is important as it allows for optimisation of the ongoing monitoring.

(A. Petersen, M. Stegger, H.B. Eriksen, S. Hoffmann, Bacteria, Parasites and Fungi, Infection Preparedness)

Summer holidays

Unless special circumstances arise, EPI-NEWS will not be published in Weeks 28-32. The Editorial Team wishes all of the now more than 10,000 subscribers and other readers a pleasant summer.

(Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention)

Link to previous issues of EPI-NEWS

5 July 2017