No 25 - 2013

Tick-borne infections in Denmark

Neuroborreliosis 2011-12

Tick-borne encephalitis 2011-12

Other tick-borne infections

Neuroborreliosis 2011-12

In 2011-2012, a total of 160 cases of neuroborreliosis (NB) were notified, including 101 in 2011 and 59 in 2012. There was a predominance of males (91 cases, 57%). A reminder of notification was sent out in 44% of the cases on the basis of a positive SSI laboratory result. As per June 2013, reminders were sent out for an additional five notifications, also on the basis of positive SSI laboratory results from 2012.

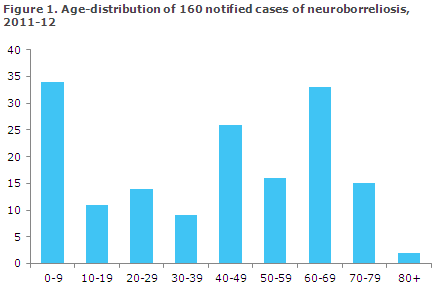

In 135 (84%) cases, the diagnosis was made by intrathecal synthesis of borrelia antibodies. Among the notified cases, 34 (21%) were younger than ten years of age, Figure 1.

Information about symptoms was available in 116 (73%) cases: 49 (31%) had facial nerve palsy, 22 (14%) developed pain in the musculoskeletal system, 10 (6%) paraesthesia, 10 (6%) headache and two (1%) developed aseptic meningitis. The remaining cases reported other neurological or unspecific symptoms. Among 34 children under 10 years of age, 23 had facial nerve palsy as their primary symptom.

The majority (n=151) were infected in Denmark, while four were infected in Sweden, three in other European countries and one in Canada. In one case, the country of infection was unknown.

Underreporting of neuroborreliosis

To assess the extent of NB underreporting, data extraction was made from the Danish Microbiology Database (MiBa) to identify patients with intrathecal synthesis of borrelia antibodies in the 2011-12 period. In this period, a total of 553 patients had a positive intrathecal synthesis, including 143 who were notified with NB, which corresponds to a 26% notification percentage.

An additional 18 clinical cases had been notified, but were not recorded in the MiBa. MiBa data are preliminary and need further validation, among others because data from Bornholm and from the catchment area of the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Herning, are missing.

Symptoms and diagnostics

The infection is caused by the spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and is transmitted by the Ixodes ricinus tick. The clinical manifestations are divided into three stages: Early localized infection which typically manifests as erythema migrans 1-2 weeks (3-30 days) after a tick bite.

The diagnosis is clinical as serological testing does not provide sufficient sensitivity in the early phase.

Early disseminated infection is observed weeks to months after the initial stage and comprises, among others, multiple erythema migrans, carditis, lymphocytoma and NB. Late disseminated infection occurs months after exposure. The clinical manifestations are chronic atrophic acrodermatitis, chronic arthritis or chronic NB.

On suspicion of NB, the diagnosis is corroborated by a positive spinal fluid test for monocytary pleocytosis and intratecal synthesis of borrelia antibodies. On suspicion of other manifestations of disseminated borreliosis, the diagnosis is made on the basis of the clinical picture in conjunction with detection of borrelia antibodies in serum.

It is important to note that, depending on the method used, IgG or IgM antibodies may be found in 4-10% of the healthy population, and serology is therefore not suitable for general screening, but should only be made on the basis of actual clinical suspicion of borreliosis. Very high IgG titres, however, strongly indicate a borrelia infection.

Commentary

Over the past ten years, an average 79 annual NB cases have been notified. In 2011, a total of 101 cases were notified. This was an increase compared with the annual number observed for the 2007-10 period, EPI-NEWS 14/11. This increase, however, did not continue into 2012.

Comparison of the number of patients with a positive intrathecal synthesis of borrelia antibodies in the MiBa to the number of notified cases suggests a likely, considerable underreporting of NB.

In connection with the upcoming revision of the notification system for infectious diseases, it will therefore be assessed if laboratory-based monitoring of patients with a positive intrathecal synthesis of borrelia antibodies should replace notification in writing by the treating physician.

It is expected that a purely laboratory-based monitoring will increase the quality and the completeness of the surveillance. Nevertheless, until further notice, NB remains notifiable on Form 1515.

Research with a view to developing a vaccine against borrelia infection has been on-going for many years, but currently no such vaccines are marketed. In a recent European study, a new vaccine based on proteins from various borrelia serotypes, including those occurring in Europe (multivalent OspA vaccine), was tested in 300 persons.

The study showed that the vaccine's adverse events profile was acceptable and that it had a sufficient antibody response. Only large randomized clinical trials will reveal if the vaccine also protects against borrelia infection, and it will therefore take several years before this borrelia vaccine may become available.

The primary preventive measure, therefore, remains avoiding that ticks become attached to the skin, e.g. by wearing suitable clothing. Furthermore, anyone spending time in woods and grass lands in the period from April to October should make sure to search their skin and scalp as the tick is particularly active in this period.

(L.K. Knudsen, T.G. Krause, M. Voldstedlund, L. Espenhain, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, R. Dessau, DCM Slagelse, S. Villumsen, Microbiology and Infection Control)

Tick-borne encephalitis 2011-12

In 2011, SSI detected three cases of tick-borne encephalitis (TBE); two men and a woman aged 20-72 years. Patients were presumably infected in known endemic areas on Bornholm, in Sweden and Lithuania, EPI-NEWS 6/12.

2012 only saw a single case of TBE in a 45-year-old woman who was presumably infected in Sweden.

Disease transmission and symptoms

TBE is caused by a flavivirus (TBE virus) and is transmitted within minutes after a tick bite. The disease presents as fever and influenza-like symptoms. After about 1-2 weeks without symptoms, the disease may progress into encephalitis in approx. one third of the cases. Particularly in the elderly, TBE may be associated with sequelae extending for several years in the form of hemiplegia and neuropsychiatric symptoms. TBE rarely takes a serious course in children below school age.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis is made by PCR for virus in spinal fluid or blood, or by ELISA for detection of specific antibodies in blood. Elevated IgM titres tentatively indicate on-going or recently recovered from infection. An IgG titre increase from the initial to the second test supports the diagnosis.

The first blood sample should be taken as early as possible in the course of the disease; the second should be taken 1-2 weeks later. On suspicion of TBE, an extra blood sample should be taken when the patient is discharged from hospital. Antibodies to other types of flavivirus and previous yellow fever or Japanese encephalitis vaccination may cross-react with TBE virus antigens, and a titre increase should therefore be detected.

A confirmatory TBE antibody neutralisation test may serve to confirm TBE specificity. Such test, however, is not standard.

Prevention and vaccination

As for other tick-borne infections, the risk of tick bites can be reduced by using boots and long trousers and by frequent inspections to brush off the ticks. There is no evidence that the use of mosquito repellents has any effect.

Vaccination may be considered in persons who are living permanently or have a fixed summer residence in areas with TBE and who regularly leave the paths of woods and scrubland. However, vaccination may also be considered in cases of behaviour associated with a particularly great risk of infection, such as forestry work, or where the woods are the fixed location for play, sport or hobby activities.

A total of three doses are given at a recommended interval of 1-3 months between the first and second dose. In cases where there is a need to achieve a rapid immune response, the second dose may be given two weeks after the first dose. The third dose is a booster, which should be given 5-12 months after the second vaccination.

To achieve immunity before the tick season starts, the first and second dose should preferably be given during the winter months and the third dose before the next season starts. Revaccination should be given at 3-5 year intervals, see the vaccine summary of product characteristics at www.ssi.dk. In case of delayed vaccination, the next vaccine should be given as soon as possible, under no circumstances should the vaccination sequence be reinitiated.

Commentary

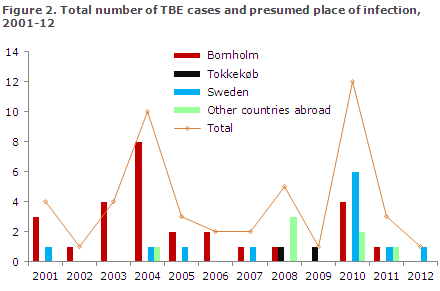

Neither 2011 nor 2012 saw any cases of TBE acquired in Denmark outside of Bornholm, where TBE occurs endemically. Consequently, no cases were found either in North Zealand or other parts of Denmark, apart from Bornholm. Since 2001, an average of four annual cases have been detected (range 1-12), Figure 2.

The increasing number of cases detected in 2010, EPI-NEWS 14/11, is attributable to the increased attention surrounding the condition following two TBE cases in 2008 and 2009, and the finding of TBE virus ticks in Tokkekøb Hegn in the same area, EPI-NEWS 35/09 (pdf).

Testing of ticks collected in 2010 and 2011 in Tokkekøb Hegn has again detected TBE virus in nymphs (young ticks), which indicates a more permanent occurrence of TBE in this particular area. Genetic analyses indicate that these TBE viruses may have originated from Sweden/Norway, whereas the TBE virus found on Bornholm may be from Finland.

The risk of human infection is considered to be very modest, as no TBE patients infected in Zealand have been observed since 2009. Physicians should, however, remain attentive to TBE as a differential diagnosis in patients with relevant symptoms and probable exposure to tick bites, particularly in this area.

(P.H. Andersen, K. Mølbak, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, A. Fomsgaard, Department of Virology)

Other tick-borne infections in Denmark

In 2011, KSL Consulting and Merial in cooperation with 22 veterinarian clinics performed a study in South and West Denmark on ticks collected from dogs. A total of 813 ticks were collected from 350 dogs.

The ticks were tested at the Laboratory of Parasitology, SSI for the occurrence of a series of micro-organisms that may cause disease in humans. DNA was extracted from the 350 tick pools and tested by PCR and subsequently by DNA sequencing to detect the presence and to determine the species. The tests demonstrated that 7% of the dogs carried ticks infected with the babesia blood parasite, 6% Babesia microti and 1% Babesia venatorum (EU1). Both species may be pathogenic in humans.

Human infection with babesia is not notifiable, but it is diagnosed at the SSI, and no cases of presumed infection in Denmark have presently been recorded. The diagnosis is made by detection through microscopy of blood smear and/or PCR, primarily based on blood.

Detection of specific antibodies may also confirm the diagnosis. Serological studies have demonstrated that the majority of cases are asymptomatic. Persons with asplenia or immunodeficiency are the primary risk group for development of symptoms following infection with this parasite. The symptoms may include anaemia, fever, rash and general malaise as in influenza. Person-to-person infection has not been observed, but the parasite may be transferred through blood transfusion.

In addition to Babesia, the ticks were tested for borrelia, Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Bartonella henselae, rickettsia and Francisella tularensis, EPI-News 7-8/13, and the following percentages of positives were found: 15%, 1%, 0.6%, 17% and 0%. For borrelia, the dominant species was B. afzelii and for rickettsia it was R. helvetica, both of which cause disease in humans. Neoehrlichia mikurensis has previously been detected in ticks collected on Bornholm, in Tokkekøb Hegn and in Viborg. Bartonella henselae is primarily transmitted from cats and is the cause of cat scratch disease, but ticks probably also play a role in transmitting the bacterium to humans, see www.ssi.dk/Service/Sygdomsleksikon and EPI-NEWS 2/05.

Commentary

The above-listed infections are not believed to occur frequently in humans. The conditions may, however, cause serious disease, particularly in asplenic persons and persons with immunodeficiency.

These infections may be taken into account when considering differential diagnostics in disease following tick bites. A total of 5% of the DNA extractions tested positive to two or three of the tested microorganisms. This suggests that there may be indication for extended diagnostic workup in cases with an atypical disease picture or lack of treatment response.

(H.V. Nielsen, Department of Paracytology)

Link to previous issues of EPI-NEWS

19 June 2013