No 34 - 2021

HPV vaccination catch-up programmes will soon expire

Acute and chronic hepatitis C, 2019-2020

HPV vaccination catch-up programmes for boys will expire soon

The offer of free HPV vaccination for boys and young men included in the catch-up programmes will expire on 31 December 2021. As some of the included persons have turned 15 years old, it is recommended that they complete a three-dose programme with an interval of 1-2-months between the first and second dose, and an interval of 3-4-months between the second and third dose. This means that their vaccination programme must be initiated no later than 31 August 2021 in order to complete the vaccinations before the free programme expires.

The catch-up programmes were introduced in February 2020 and cover:

- Boys born between from 1 January 2006 and 30 June 2007.

- Young men who are attracted to men and who turned 18 years old on 1 January 2020 or later, but not 26 years old before 1 January 2020, i.e. born between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2003.

The offer expires when the person turns 26 years old.

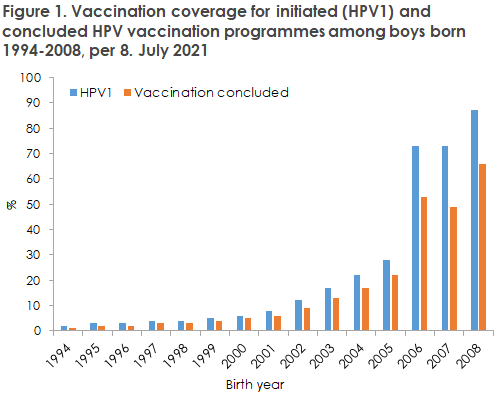

As per 8 July 2021, 73% of boys born in 2006 have initiated an HPV vaccination programme (HPV1), whereas 53% have concluded it. For the 2007 birth cohort, the coverage is 73% and 49%, respectively. Among the older birth cohorts of the second catch-up group, vaccination coverage cannot be calculated as the criterion “attracted to men” is established in consultation with the person’s GP. However, vaccination coverage of entire birth cohorts can be calculated, and here the coverage of HPV1 increases from 2% among boys born in 1994 to 17% among boys born in 2003. The same pattern is seen for concluded vaccination courses, Figure 1.

The HPV vaccination coverage can be seen at statistik.ssi.dk.

Read more about HPV vaccination for girls and boys at ssi.dk.

(K. Finderup Nielsen, P. Valentiner-Branth, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention)

Acute and chronic hepatitis C, 2019-2020

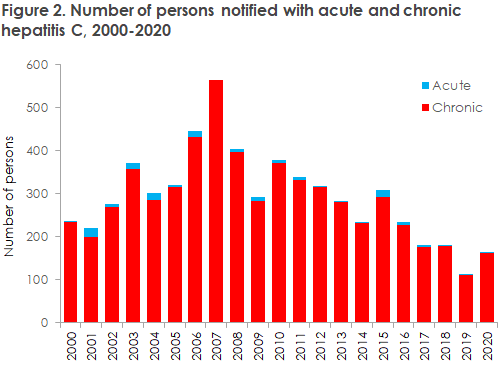

In 2019, the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention received 123 notifications of chronic hepatitis C. In 2020, the corresponding figure was 165 notifications.

Among these, 11 of the cases in 2019 and three of the cases in 2020 were notified as acute hepatitis C; among these, seven and three, respectively, were men. With respect to chronic hepatitis C, a total of 111 cases were notified in 2019 and 161 cases were notified in 2020; among these cases, 79 (71%) and 117 (73%), respectively, were men.

For a detailed epidemiological account of the incidence in 2019 and 2020, please see annual reports on disease incidence.

The number of notified hepatitis C cases was markedly lower in 2019 than in 2018 (61% of the 2018 level). In 2020, the number of notified cases increased somewhat but remained below the 2018 level. Overall, the number of notifications has followed a decreasing trend since 2007, apart from slight increases in 2015 and once more in 2020, Figure 1.

For chronic hepatitis C, the median age has increased steadily from nearly 40 years in 1991 to the current nearly 50 years, and from nearly 35 years to nearly 45 years for acute hepatitis C.

The notification incidence was highest on Funen and in West Jutland. The largest increase, however, was observed in West and South Zealand. The relatively high incidence on Funen may likely be explained by a particularly intensive hepatitis C tracing effort in the context of the project “C Free South”and a special effort made to ensure that cases are notified.

The total incidence increased from 1.9 in 2019 to 2.8 in 2020 despite the COVID-19 epidemic. No obvious explanation exists for this increase, and it may simply be a common fluctuation.

Country of infection

Country of infection was unknown or not stated in 23% of the notifications in 2019 and in 14% of the notifications in 2020.

For chronic hepatitis C, most of the cases for which the country of infection was stated had become infected in Denmark. This applied in 2019 (66 cases, 59%) as well as in 2020 (117 cases, 72%). In 2019, 18% had presumably become infected abroad, whereas this was the case for 14% in 2020.

Many different countries from the entire world were stated as the country of infection in cases not infected in Denmark, but a slight infection preponderance was seen for Russia (a total of seven cases), Pakistan (a total of four cases) and Thailand (a total of four cases).

The Danish Health Authority recommends that migrants from high-endemic countries such as Egypt, Pakistan and Rumania be tested for hepatitis C at their first contact with Danish healthcare, ideally when arriving to Denmark.

Mode of transmission

Mode of transmission was unknown or not stated in 16% of the notifications in 2019 and in 11% of the notifications in 2020.

Intravenous drug use

Among the cases for which the mode of transmission was given, intravenous drug use was stated as the transmission mode in 83 (67%) cases in 2019 and in 124 (75%) cases in 2020. This is on a par with the preceding years; and intravenous drug use therefore remains the most frequently recorded source of hepatitis C infection in Denmark.

Presumably, transmission between persons with intravenous drug use is therefore the chief cause of hepatitis C in Denmark. Therefore, we still recommend that persons with previous or current intravenous drug use are screened for hepatitis C. A study by Øvrehus et al. from 2018 found that two thirds of present and previous intravenous drug users had been exposed to hepatitis C virus (HCV).

Sexually transmitted infection

In 2019 and 2020, a total of seven cases and one case, respectively, were notified as presumably having been infected through sexual contact between MSM. Among these eight cases, six were notified as acute cases, and three of the cases were detected in persons with concurrent HIV infection, whereas the rest were not infected by HIV. The relatively high occurrence of non-HIV infected people compared with previous years may possibly be caused by more MSM undergoing hepatitis C testing when they receive prophylactic HIV treatment (PrEP), which may thus indicate an increased occurrence of undiagnosed asymptomatic hepatitis C among MSM.

Recent years have brought reports of hepatitis C outbreaks among MSM in connection with so-called chemsex; a concept describing the use of drugs to enhance and extend sex. It is known that chemsex is also practiced in Denmark, primarily in larger cities. The notifications made to the SSI do not always state if infection in the notified hepatitis C cases among MSM was transmitted through chemsex. It is important to be aware of the risk of infection through chemsex and to disseminate knowledge of how such infection may be prevented.

Heterosexual transmission was stated as the presumed mode of transmission in tree cases in 2019 and in one case in 2020.

Mother-to-child transmission

Mother-to-child transmission during labour was stated as the presumed mode of transmission in zero cases in 2019 and in five cases in 2020, all of which were adult cases. Among the five cases notified in 2020, four were born abroad, whereas one case was an adult who had presumably become infected during labour in Denmark by the mother who was a former drug user.

Pregnant women do not routinely undergo hepatitis C testing in Denmark. This is partly because of the low occurrence of hepatitis C among women of childbearing potential, partly because of the low risk (5-10%) of transmitting the virus to the child. Furthermore, infection in connection with pregnancy and labour may not currently be prevented, as is the case for hepatitis B.

In the US, trials are ongoing in which pregnant women in their third trimester receive hepatitis C treatment to prevent mother-to-child transmission. Women who are known to have hepatitis C are not recommended to avoid either pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Other modes of transmission

In 2019, tattooing was stated as the presumed mode of transmission in four cases (including three cases who had presumably become infected in Denmark; two many years earlier and for one case the time of infection was not stated) and one case who had presumably become infected abroad. In 2020, tattooing was the presumed mode of transmission in seven cases, including six cases who had presumably become infected abroad and one case who had presumably been infected in Denmark and for whom the time of infection was not stated. The Danish Tattooing Act establishes a number of hygiene requirements for tattooing providers and, as per 1 January 2021, all tattooists affiliated with a registered tattooing provider and who do tattoos occupationally must have completed a hygiene course.

Nosocomial transmission (i.e. transmission in connection with procedures provided by healthcare workers, e.g. blood donation) was stated as the presumed mode of transmission in two cases in 2020, both of which occurred abroad. No cases of presumed nosocomial transmission were notified in 2019.

Elimination of hepatitis C

Denmark has joined the WHO objective to eliminate hepatitis C before 2030. In practice, with 2016 as the base year, this means that the incidence needs to decline by 90%, that 90% of the infected persons need to have been diagnosed and that 80% of these need to have been treated.

For a number of years, the number of notified hepatitis C cases has followed a declining trend, which may be owed to an decreasing incidence among young drug users, among others because fewer (young) drug users inject their drugs. This is also reflected in a steadily increasing age among the notified persons. Access to drug consumption rooms in major cities and an emphasis on access to clean injection kits have also reduced the risk of infection. Furthermore, more persons are in treatment and the overwhelming majority of hepatitis C patients in outpatient treatment are now estimated to have been cured. All things being equal, this reduces the infective pressure.

As it is not yet possible to monitor hepatitis C laboratory results for most Danish regions, and notification reminders therefore cannot be sent out, it is estimated that the number of hepatitis C cases is far higher than the figures accounted for herein. A Danish study from 2016 based on so-called capture-recapture calculations and data from multiple registers assessed that approx. 10,000 persons are living with chronic hepatitis C in Denmark, corresponding to 0.21% of the population. Furthermore, the study estimated that approx. one fourth of these people have yet to be diagnosed and that only about half of the diagnosed cases are notified. Due to the low notification percentage, it is difficult to interpret the differences in the incidence of notified cases shown in the Annual Report. Thus, these differences may reflect inter-departmental differences in notification procedures as much as they reflect real incidence differences.

A laboratory-based - and therefore more accurate - monitoring may help provide a better estimate of the total number of infected people in Denmark and thereby an improved estimate of how many need treatment. Furthermore, laboratory-based monitoring may help determine if additional initiatives are needed to meet the WHO objectives that Denmark has an obligation to reach no later than by 2030.

Hepatitis C infection is still chiefly associated with intravenous drug use, and considerable stigma is associated with both intravenous drug use and hepatitis C. Some infected persons may have become infected long ago and may remain unaware of this; this group includes people who are no longer drug users.

In order for Denmark to meet the WHO objective to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, all potentially infected people must be offered testing and treatment. We take this opportunity to underpin once more that hepatitis C treatment has been made available to everyone in Denmark and that its cost has declined considerably.

Furthermore, the prophylactic measures against hepatitis C include making available sterile injection kits to persons with an intravenous drug use. The Danish Health Authority has published an inspirational catalogue for municipalities aiming to qualify their damage-reducing efforts in relation to the dispensing of sterile injection kits by describing the possible contents of a dispensing practice.

(M. Aabye, M. Button, S. Cowan, Department of Infectious Epidemiology and Prevention, A. Øvrehus, P. Brehm Christensen, Department of Infectious Medicine, Odense University Hospital)