No 21/22 - 2020

Screening of pregnant women for hepatitis B, HIV and syphilis, 2019

Screening of pregnant women for hepatitis B, HIV and syphilis, 2019

|

Screening of pregnant women for hepatitis B virus (HBV) was introduced on 1 November 2005, and screening for HIV and syphilis was initiated on 1 January 2010. The 2019 annual report is now available. Due to low figures, some of the information included in previous reports about pregnancy screening has been left out in this report in pursuance of statutory GDPR provisions. Thus, it has not been possible to describe the few cases in which the screening course was incomplete and caused transmission of infection that could have been avoided.

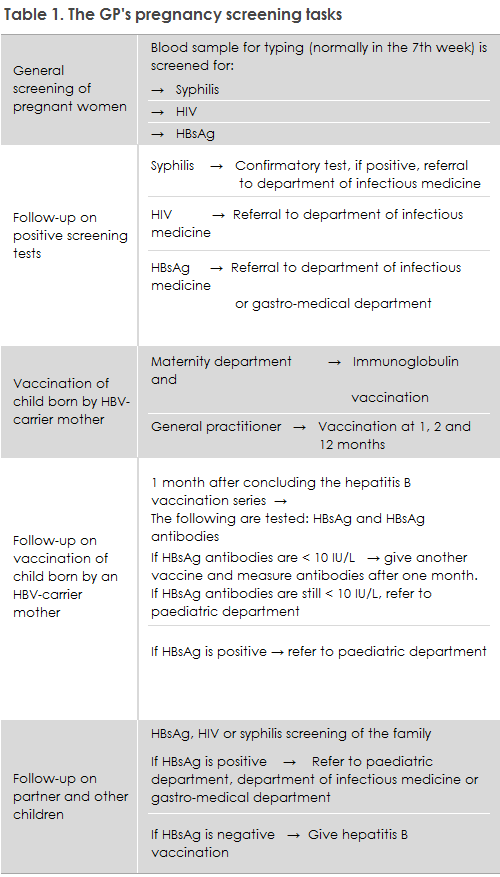

The general practitioner's tasks in relation to pregnancy screening are presented in Table 1.

In 2019, a total of 67,994 blood type analyses were performed in pregnant women. Among these women, 67,975 (99.9%) were tested for hepatitis B (HBV), 67,824 (99.7%) for HIV and 67,800 (99.7%) for syphilis. Thus, the overwhelming majority of pregnant women accept the offer of hepatitis B, HIV and syphilis screening; and therefore nearly all potential cases of mother-to-child transmission with the three conditions can be avoided.

Pregnant women who stay in the country as undocumented immigrants may be examined by a physician at a Red Cross health clinic in Copenhagen or Aarhus. Here, pregnancy screening is also offered, but this service does not form part of the public offer of care for childbearing women. The maternity ward shall obtain blood samples to test for syphilis, hepatitis B and do a rapid HIV test of any woman in labour with an unknown status admitted to the ward.

In 2019, six out of 11 of the pregnant women with syphilis were of Danish origin. This shows that, in Denmark, syphilis is not exclusively a condition that occurs among men who have sex with men or immigrants from high-incidence countries; it has been re-introduced among heterosexual Danes.

In case of a positive screening result, the pregnant woman needs to be informed that the majority of screening findings are false positives, but that an extended analysis is needed to confirm or disprove the result. Furthermore, the pregnant woman needs to be informed that - if she does indeed have syphilis - the condition is treatable so that she will not transmit the condition to her child. Additionally, the pregnant woman needs to be informed of the importance of having her sexual partner(s) tested and, if needed, treated.

It is important that treating physicians refer any pregnant woman who has had one of the three infections detected in the screening to the relevant specialist departments, even if the woman in question has no infection symptoms, Table 1. Pregnant women with a high HBV virus amount (>106 IU/ml) may typically be offered treatment at approx. 28 weeks of gestation, which may reduce the risk of intrauterine transmission, cf. guidelines on the treatment of hepatitis, prepared by the Danish Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology (in Danish language).

In pursuance of the Danish Health Authority's guideline on general screening of pregnant women for infection with hepatitis B, HIV and syphilis, the pregnant woman's partner and other children should have blood tests taken.

According to the Danish Health Authority’s guideline on HIV, hepatitis B and C virus published in 2013, all children born by HBV carrier mothers who receive hepatitis B vaccination at birth and subsequently at the GP should be tested to confirm that the vaccination has taken and to test for current infection one month after the vaccination series has been concluded, Table 1, i.e., when the child is 13-15 months old. This is necessary because inter-uterine infection occurs in some children, in which case the vaccine is ineffective. The responsibility for performing this test lies with the GP, Table 1. If the child has become infected, he or she should be referred to a paediatric department. If the child is insufficiently covered (anti-HBs <10 IU/L) despite the vaccinations, an additional vaccination may be given after which antibodies are measured one month later. If the child is still insufficiently covered, he or she is referred to a paediatric department. Statens Serum Institut (SSI) sends out reminders to the GPs about hepatitis B vaccination of children born by hepatitis B-carrier mothers and about subsequent testing of these children.

We have established that children who are vaccinated against hepatitis B at birth are typically not registered in the Danish Vaccination Register (DVR) despite the fact that doctors, nurses and midwives who administer the vaccine have a duty to notify. In addition to the fact that the parents cannot see that their child has been vaccinated when the vaccination has not been registered in the DVR, a vaccination course also cannot be established in the DVR. If a vaccination course is established, the parents as well as the GP will automatically gain access to the dates at which the next vaccinations are to be given. Therefore, the Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention has decided to register hepatitis B vaccinations in the DVR on behalf of any places of birth that have not already done so. This, however, is not possible in cases in which the place of birth has failed to fill in the form about immunisation of the neonate. Such forms must be forwarded to the SSI, which can be done electronically.

(A.K. Hvass, M.S. Jørgensen, S. Cowan, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention, S. Hoffmann, Department of Bacteria, Parasites and Fungi.