No 15 - 2014

European Immunisation Week

Outbreak of ebola virus disease in West Africa

European Immunisation Week

Once again, week 17 marks this year's European Immunisation Week. During the week, the WHO, the ECDC and the individual member countries will focus on the childhood vaccination programme and its successes and challenges.

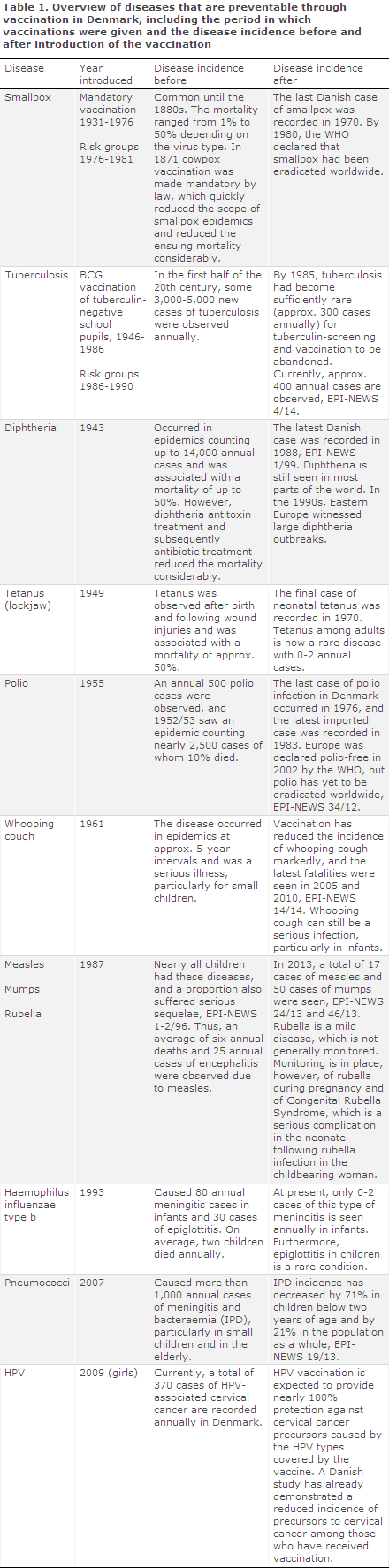

The Danish childhood vaccination programme is an offer to all children of free vaccination currently comprising a total of nine infectious diseases. Additionally, girls are offered vaccination against cervical cancer. Smallpox has been eradicated, and tuberculosis vaccination has been abandoned, see Table 1.

Vaccinations serve to prevent disease that may severely affect the child. Some childhood diseases are very infectious, and nearly all children will be affected by them sooner or later if they are not vaccinated. This applies to measles, mumps, rubella and whooping cough. Without vaccinations, diphtheria and polio epidemics would occur every few years, and thousands would fall ill. In the case of meningitis caused by haemophilus influenzae type b or pneumococci, only a limited number of persons would be affected, but as the infection is extremely severe and carries a risk of death or permanent sequelae, all children are offered vaccination against these types of meningitis, which occur frequently in childhood.

Any child following the Danish childhood vaccination programme will have good protection against these nine (ten) diseases. But a vaccination programme presupposes that nearly everyone is vaccinated; if this is not the case, the diseases will still be able to spread and the few who have not been vaccinated will not be protected by herd immunity. Even though many of the diseases seem to be well-controlled in Denmark (e.g. diptheria and polio), the diseases do occur in other parts of the world, and exposure to infection during travels is possible.

It is a WHO objective to eradicate polio within a few years. The hope is that vaccination may be abandoned, which was the case for smallpox in 1981 when this disease had been eradicated.

Furthermore, it is the WHO's objective to eliminate measles and rubella in the Europe Region by 2015. If this objective is achieved, only imported cases of measles will be seen in Denmark, and measles will be unable to spread owing to the high level of immunity in the population.

Before a recommendation is made to add a vaccination to the childhood vaccination programme, the following issues are considered: seriousness of the disease, disease burden, infection risk and the magnitude of any side effects associated with the vaccine. Vaccination against a disease is not introduced simply because a vaccine is available on the market, or for socio-economic reasons. Vaccines are introduced because the diseases can have serious consequences for the affected children and should therefore be prevented. In addition to the beneficial effect achieved for the vaccinated child, vaccination carries an indirect protective benefit for children who cannot be vaccinated, e.g. due to immunosuppression, children who are too young to receive vaccination and children in whom the vaccination has not been effective.

In Denmark, vaccination is voluntary and rests with the general practitioners. The doctor who performs the vaccinations is also under an obligation to inform both the parents and the child about the vaccination, and about common side effects. Before a vaccination is administered, many parents will have talked to a health visitor or to other parents about the vaccinations. As from 15 years of age, children have co-determination in pursuance of the Danish Health Act.

Commentary

This year, the European Immunisation Week focuses particularly on outbreaks of childhood diseases such as measles and mumps in teenagers and young adults which at times have serious consequences. The 2011 measles outbreak in Denmark was the largest since 1996, EPI-NEWS 24/11. In this outbreak, which counted a total of 84 reported cases, approx. one third of the cases were young adults (all but one were unvaccinated) 70% of whom were admitted to hospital. Measles is one of the most infectious viruses known to man, and a 95% coverage is needed for both MMR1 and MMR2 to achieve the WHO's objective of eradicating the disease. According to the Danish Vaccination Register, MMR1 coverage is currently 89% and MMR 2 coverage at 12 years of age is 83%. These are minimum estimates, and a recent survey renders probable that the real coverage for vaccinations given up to the age of five years is 3-4 percentage points higher owing to lacking registration of the given vaccinations, EPI-NEWS 20/12. Furthermore, the survey showed that oversight is the primary cause of lacking 5-year vaccination, which is a DTaP-IPV revaccination with a recorded 82% coverage.

To increase the vaccination coverage, the Danish Parliament (Folketinget) and the Danish Ministry of Health have decided that as from mid-May 2014, Statens Serum Institut will send out reminders to parents of children who will turn 2 years, 6 1/2 years and 14 years old, who have not yet received all the vaccinations recommended under the Danish childhood vaccination programme. Citizens will then have the opportunity to make an appointment with their GP to receive any missing vaccinations. Citizens will be given the opportunity to opt out so that they do not receive the vaccination reminders. Statens Serum Institut has access to data on children's vaccinations in the Danish Vaccination Register (DVR).

Since February 2013, citizens have had the opportunity to consult their own and their children's vaccinations (for children born after 2004), and healthcare staff have access to their patients' vaccinations given as part of the Danish childhood vaccination programme as from 1996. If a vaccination has been given, but has not been recorded in the DVR, citizens can add the vaccinations to the DVR for any children born after 2004. Similarly, doctors can correct any errors and add vaccinations to the DVR via fmk-online.dk.

The Danish vaccination programme has enjoyed considerable success which can hardly be matched by any other healthcare intervention in terms of avoided morbidity and mortality. Owing to many years with a high vaccination coverage, the diseases have now been eradicated, nearly eradicated or have become rare. This can, in turn, entail a communicative challenge for healthcare staff meeting with parents who may find that the risk of the side effects associated with vaccination outweighs the risks posed by the diseases. Apart from the diseases which have been eradicated, the micro-organisms still exist and may cause infection, e.g. in connection with travels abroad, or they may give rise to regular epidemics if the coverage decreases and a large proportion of the population become susceptible to the disease again.

(P. Valentiner-Branth, T.G. Krause, P.H. Andersen, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, SSI)

Outbreak of ebola virus disease in West Africa

The current outbreak of ebola virus disease (EVD) at present counts cases from the West African country Guinea and neighbouring Liberia. Ebola virus (EV) transfers through contact with patients' bodily fluids and under normal conditions, the risk of infection is therefore minimal. Consequently, spreading outside the affected area in West Africa is very unlikely.

No travel restrictions have been introduced for the affected countries.

About ebola virus and ebola virus disease

EV belongs to the filovirus group and along with Marburg virus and Lassa fever virus comprise the three African haemorrhagic viruses. Since the first EVD outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1976, five species of EV have been identified, including Zaire EV, Sudan EV, Reston EV, Tai forest EV and Bundibugyo EV.

Presumably, some types of bats are natural hosts of this virus, from where it may on rare occasions transfer to other animals or humans.

After a 2-21-day incubation period, EVD presents with sudden-onset fever, muscle aches, general fatigue, headache and a sore throat. These symptoms are followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash and affected liver and kidney function. In some cases, severe haemorrhaging from inner and outer bodily cavities is observed, and the disease may progress into multi-organ failure. No vaccine or other specific treatment exists apart from fluid management and other supportive measures. Mortality ranges from 50% to 90% depending on the EV species. Genetic testing of virus from the current outbreak has shown that it is very similar to Zaire EV which has the highest mortality of any haemorrhagic fever virus.

Risk of infection

In practice, EV transfers through close contact with diseased and dead patient's bodily fluids such as blood and secretions like vomit and faeces. The patients' secretions are more infectious late in the course of the disease as the viral load is greater at this point.

The infection risk is at its highest in cases of massive contact to the patient's fluids and secretions, and cases are therefore seen among healthcare workers who are not wearing protective equipment and relatives who have had close contact to patients, or among persons who have participated in burial ceremonies, e.g. have prepared a body for burial. Furthermore, cases have been associated with the use of contaminated syringes or other medical utensils.

Healthcare and laboratory staff and any persons handling the dead should wear personal protective equipment (gloves, masks, coveralls, eye protection) when they may come into contact with blood and secretions from patients who have had or may have had EVD.

Foreign travel advice

The WHO recommends no restrictions on travel to or trade with the affected countries. It is unlikely that the virus will spread to to Europe, including Denmark.

Persons who are currently staying in the affected countries should avoid direct contact with persons with EVD or dead persons, including bodily fluids and secretions from diseased persons. Furthermore, contact should be avoided with syringes and other objects which may have become contaminated by blood or other body fluids. Sexual contact with persons who have had or may have had EVD should be avoided. Finally, travellers to and persons staying in the affected countries should avoid contact with wild animals, living as well as dead. Ebola virus is destroyed by fat solvents such as hand soap and particularly alcohol.

In case of disease, you should contact local healthcare for help. You should always contact your GP or a vaccination clinic for advice concerning vaccinations, malaria prevention and any other travel advice before travelling to Africa.

Diagnostics and duty of notification

Generally, anyone returning from Africa with a fever should see a doctor. The reason for this is that such visits will allow the doctor to rule out malaria or other serious infectious diseases.

As ebola virus is not particularly infectious, it is unlikely that fever or other signs of infection in a person returning from a vacation, culture travel or normal work-related travel should be caused by ebola virus.

Statens Serum Institut has diagnostic preparedness services for patients who are suspected of EVD. These preparedness services include epidemiological advice in connection with indication for sampling.

Samples may be drawn using special sampling tubes with transport medium allowing for standard rapid transport to Statens Serum Institut. Furthermore, tests are made for other more common causes of fever in patients who have returned with relevant exposure.

In case of reasonable suspicion of EVD, the case shall be notified by phone and in writing to the Medical Officers of Health in the area where the patient resides and in writing to Statens Serum Institut, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, in accordance with Executive Order on Physicians' Notification of Infectious Diseases, etc.

Commentary

Several international organisations are currently assisting the local health authorities in the affected countries with a view to controlling and containing the outbreak. This is done by isolating any suspected cases of EVD and by monitoring any contacts to diseased persons in the incubation period, which is up to 21 days. The coming weeks will likely bring more detected cases, until the infection chain has been effectively broken.

This is the first time EVD has been observed in West Africa. Previously, outbreaks have been recorded in Central and East Africa. All of these outbreaks were controlled through precautions as those described above, but the handling of the outbreaks has, of course, been a considerable challenge to the healthcare services of these socio-economically disadvantaged countries.

For a detailed status on the disease outbreak, please refer to WHOs Global Alert and Response website, to the ECDC, to the theme on ebola virus on the SSI's website and to the outbreak description at "Rejser og smitsomme sygdomme" (Danish for: Travel and infectious diseases).

(Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, SSI)

Link to previous issues of EPI-NEWS

9 April 2014